2019 Economic Vulnerabilities: Part Two

The first part in this series examined a growing vulnerability in the stock market: the current cycle’s price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio is at a staggering height and corporations are using their earnings for short-term focused financial engineering rather than increasing their intrinsic value.

In this installment, we look at the non-financial corporate bond market to analyze a second vulnerability in the economy. A decade long credit boom has eroded investors’ standards, which has contributed to the development of an enormous corporate debt bubble among the lowest level of investment-grade issuers (BBBs) and speculative-grade corporations. As this article will discuss, economists who have studied credit cycles have strong evidence that the current cycle is nearing the end of its expansion. With trillions of U.S. dollars invested in the corporate debt bubble, a slowing economy may spell calamity and a deep recession.

“In the wake of the most severe downturn since the Great Depression, all the elements that led to the last recession are back: credit rating agency leniency, easing underwriting standards, increased investor risk tolerance and a looming multi-trillion dollar debt bubble.

The $9 Trillion Corporate Debt Bubble

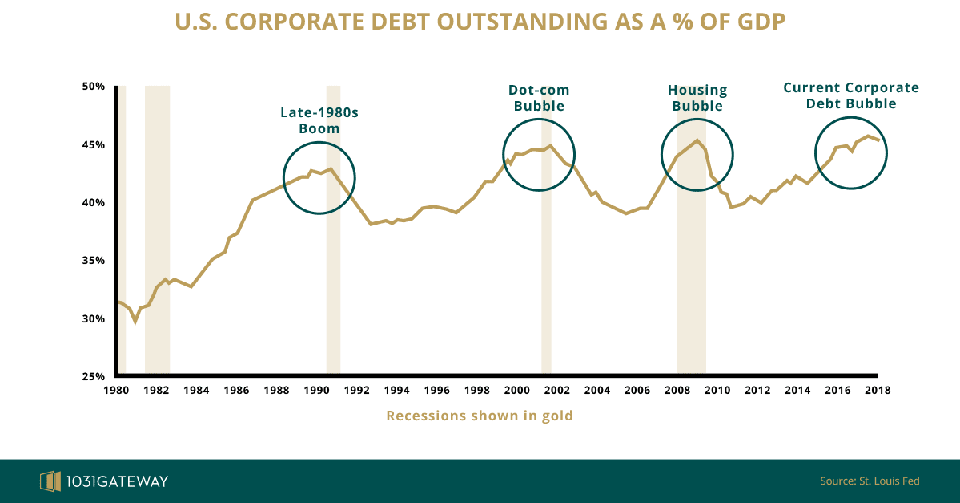

On the brink of the last financial crisis, non-financial corporations were carrying a debt load of $4.9 trillion. Research from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association shows that as of November ‘18, the debt has surged 86%, reaching $9.1 trillion. This has lifted the amount of outstanding U.S corporate debt as a percentage of GDP to an unprecedented height, above 45%. The debt relative to GDP ratio indicates historically weak balance sheets for U.S. corporations. Steve Blitz, the chief U.S. economist at TS Lombard, points out that the multiples of debt relative to cash signals that “corporations are borrowing against their net-worth, as opposed to borrowing against cash-flow and income, which in effect is the same thing households were doing in 2004, 2005, and 2006.”

Economists have said that the massive $2.1 trillion cash pile that American corporations are holding is more than enough security to cover their debt obligations, but a report from Barron’s reveals that more than half of that cash, $1.2 trillion, “is held by just 25 companies or 1% of the issuers.” Remove those 25 companies, and “more than 450 investment-grade companies had cash-to-debt ratios more similar to those of speculative-rated issuers—such as Junk—than to their investment-grade cousins in the top 1%.” The sweeping majority of corporations that currently qualify as investment-grade carry irresponsible debt.

Although the average net leverage for BBBs has nearly doubled since 2000, leniency by rating agencies has allowed BBB corporations to maintain their “good” investment-grade. Perhaps rating agencies have taken the word of corporations that they will slow debt issuance in 2019 and are counting on the economy to remain healthy enough to help BBBs pay their obligations. All the while, BBB corporations continue to issue debt (such as BBB, Anheuser-Busch InBev, $15.5bn bond offering in January) and the slice of corporate debt one level above junk continues to grow.

(For investors still taking rating agencies at their word, I’d suggest a quick review of the broad definition they gave “low risk” leading to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis.)

The Growing Share of Risky Bonds

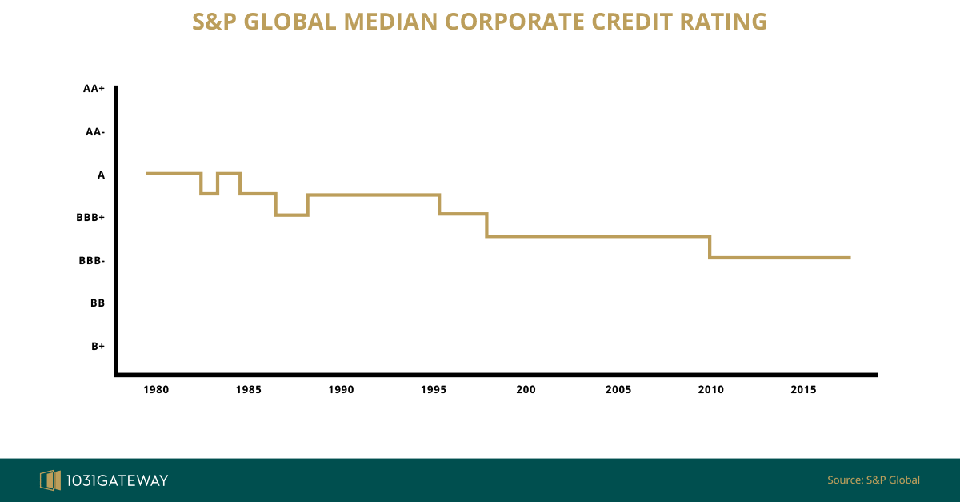

Globally, the median corporate-credit rating has been in a steady decline for decades. The Economist offered the following chart from S&P Global that shows the steady decline in median bond’s rating since the 1980s, dropping from A to BBB- corporate-credit score.

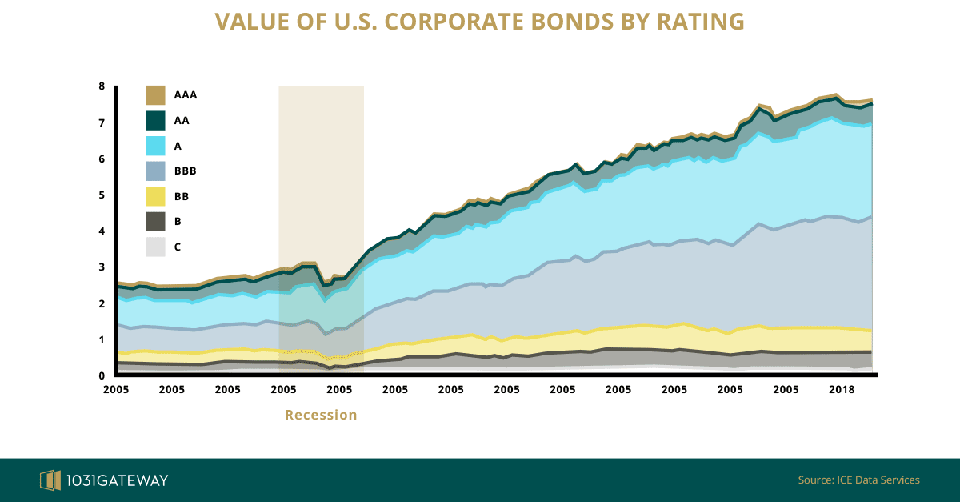

In the U.S., the rate that debt has been ballooning at the lowest investment-grade level has accelerated since the last recession. In a conference call, David Rosenberg, chief economist at Gluskin Sheff & Associates, pointed out the extent to which the BBB bond market has grown: “the BBB component, which is one notch away from being downgraded to junk, started the cycle 30% share of investment-grade and it’s now over 50%.”

The current flow of credit to corporations with weak balance sheets is the probable outcome of a robust and prolonged credit cycle, according to research by economists Robin Greenwood and Samuel G. Hanson. Their research (a study of credit cycle data ranging from 1926 to 2008) has found a correlation between aggregate credit in the economy and the corresponding quality of prolific debt issuers. Here’s what they saw: “when aggregate credit increases, the average quality of issuers deteriorates.”

The current decade long economic expansion and historically low-interest rates have produced a credit boom, which has increased corporations’ financial wherewithal and reduced the perceived risk of debt default. This has squeezed the spreads on bond yields of all classes and has subsequently incentivized investors searching for larger returns to snatch up bonds in speculative-rated corporations.

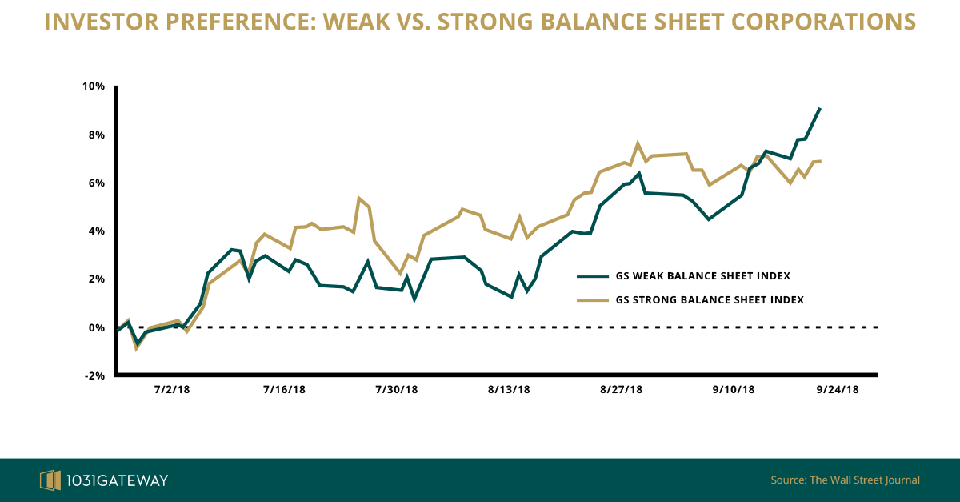

Last year, the Wall Street Journal posted a chart that showed investor’s preference for corporations with more debt leverage in 2018:

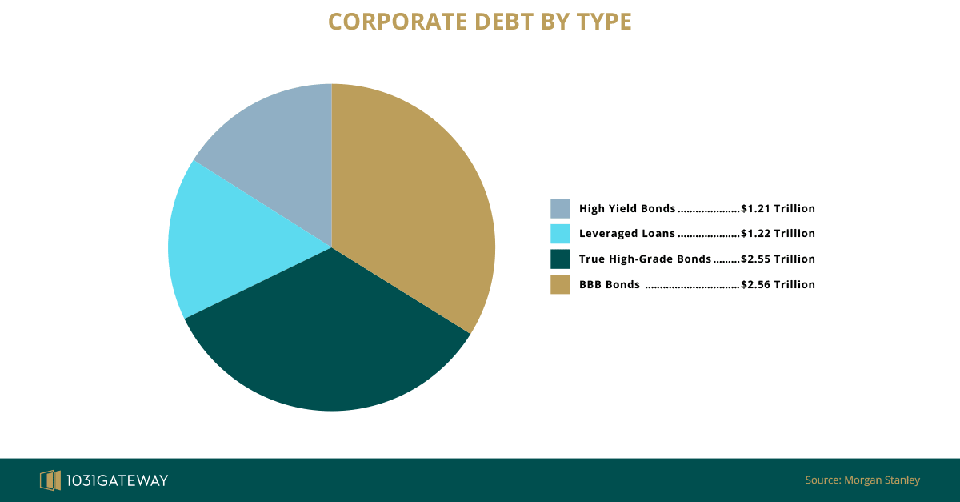

Preference for bonds of corporations using higher levels of leverage indicates a high credit market sentiment among investors. This has transformed the market: corporations with weak balance sheets have taken the majority share of the total corporate bond market. BBB’s lead in size, but as the chart below shows, highly leveraged companies rated high yield (“junk bonds”) and leveraged loan corporations make up a significant portion of the four largest corporate debt sectors.

(Just how confident are investors feeling? The leveraged loan market is where companies with balance sheets too weak to qualify as a junk bond go for financing, and it's bigger than the high yield market!)

The growing corporate debt load in speculative-credit corporations caught the attention of The International Monetary Fund (IMF) who issued this alarming statement last year: “A period of high credit growth is more likely to be followed by a severe downturn or financial sector stress over the medium term if it is accompanied by an increase in the riskiness of credit allocation.” The IMF is right to be concerned with what they’re seeing. In the wake of the most severe downturn since the Great Recession, all the elements that led to the last recession are back: credit rating agency leniency, easing underwriting standards, increased investor risk tolerance and a looming multi-trillion dollar debt bubble.

Low Corporate Bond Spreads

Investors will often incorrectly assume that thin yields are the price they should accept for the security of a corporate bond in a robust and expanding economy. But, in fact, a period of thin yields (a sign of strong credit sentiment) has been proven to be followed by an economic slowdown. The National Bureau of Economic Research, who have studied credit cycle data running from 1929 to 2013, claim:

“When corporate bond credit spreads are narrow relative to their historical norms and when the share of high yield (or “junk”) bond issuance in total corporate bond issuance is elevated, this forecasts a substantial slowing of growth in real GDP, business investment, and employment over the subsequent few years.”

Currently, bond spreads are not paying yields that keep up with historical norms. Since 1990, highly rated Moody’s Aaa corporate bonds have averaged 1.4% points above the 10-Year U.S Treasury Bonds (which are considered “riskless”); today, the spread is down to 1%. Perhaps more surprising is the thinning spread between investment rated corporate bonds and riskier high yield corporate bonds: since 1990, the spread between Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Bond Index and Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate High Yield Bond Index has averaged 4.4% points; today, it’s just over half of that, 2.5% points.

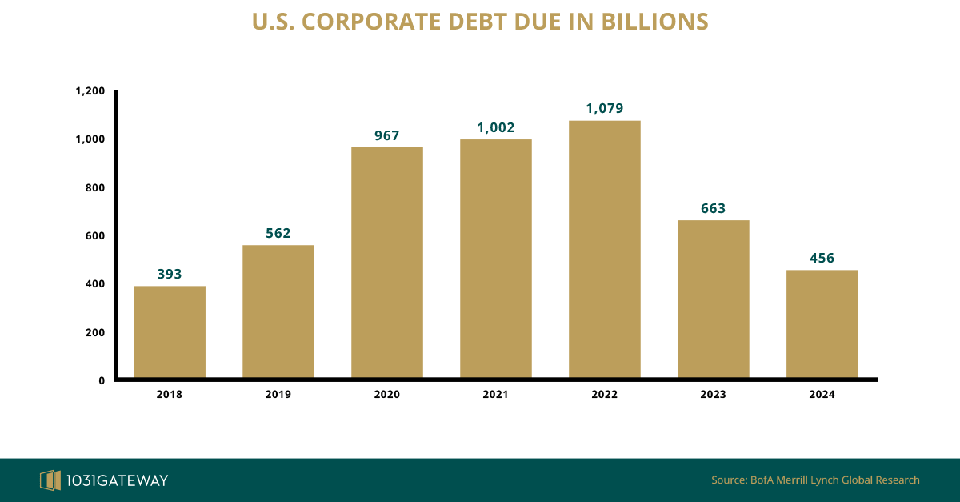

The, “substantial slowing of growth in real GDP, business investment, and employment over the subsequent few years,” that current credit conditions are forecasting, will occur at a very inconvenient time for all of the highly leveraged corporations. Trillions in corporate debt are due in the next three years.

If interest rates rise too fast or the economy slows too quickly, investors, who have been tolerating high-risk and low-yields, may be stuck with paper for defaulted corporations. If more than a small-minority of BBBs are downgraded to junk due to defaulting on debt, the high yield market may become oversaturated, increasing spreads and handing significant losses to investors.

With mounting evidence of a nearing economic slowdown and trillions of debt maturing, investors should pare down on corporate bonds, at least until spreads increase and they are adequately compensated. But according to Greenwood & Hanson’s research, corporate bondholders are unlikely to liquidate their holding until a high fraction of firms default. To their detriment, investors are prone to mispricing bonds because they use “backward-looking risk management systems” when extending credit. They over-extrapolate a small data set of recent “good-times” (low corporate default rate) to develop firm conclusions that underestimate future risks.

Simply avoiding corporate bonds is not enough of a hedge to protect investors from the potential effect of a popped corporate debt bubble. Former FED Chair, Janet Yellen described her concern during a lecture at CUNY in New York last year: “Corporate indebtedness is now quite high and I think it’s a danger that if there’s something else that causes a downturn, that high levels of corporate leverage could prolong the downturn and lead to lots of bankruptcies in the non-financial corporate sector.” A prolonged downturn is more than most investors, even those outside of the corporate debt bubble, are currently prepared to endure.

In the next post, I’ll outline a proven strategy to protect investors capital and income through the trough of a future deep and prolonged recession.